- My MOC

- Directory

Menu

4 MIN READ

4 MIN READ

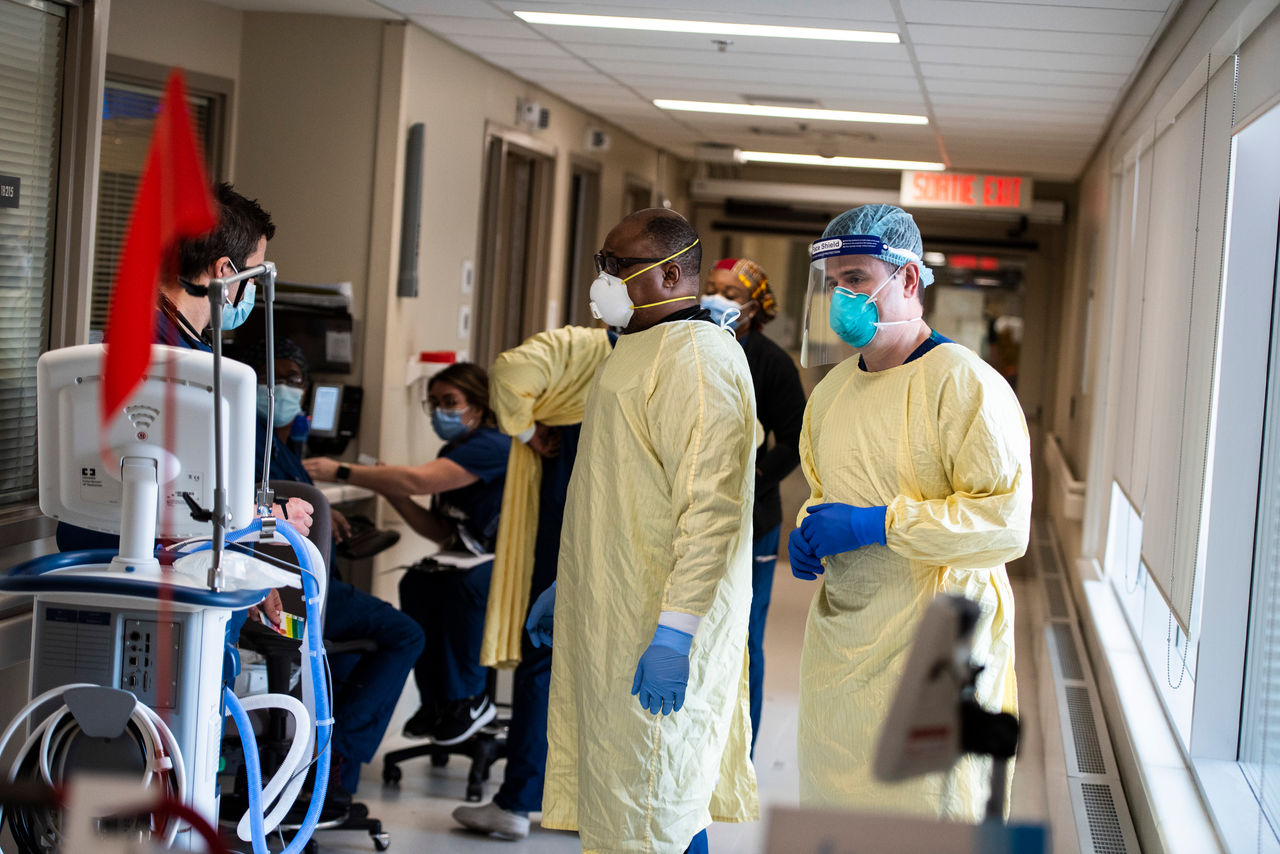

Canada is facing a serious health human resource crisis in many professions, profoundly affecting nursing and medicine. The Canadian Nursing Association estimates a shortage of 60,000 nurses alone. While it is difficult to quantify the shortage of doctors, Canadian Medical Association data shows that Canada has 2.7 physicians per 1,000 population (including residents) compared to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development average of 3.5, meaning that Canada’s physician to population ratio ranks 29th out of 36 nations.

In medicine, the largest gaps are in primary care, with an estimated 20 per cent of Canadians unable to find a family physician, but shortages and maldistribution of specialists is also a serious problem. From community clinics to hospitals, health care professionals in Canada are experiencing high levels of burnout exacerbated by shortages and urgent attention is required.

The reasons for physician shortages are multifold, including a history of training fewer Canadian physicians than the population requires, high hurdles for international medical graduates (IMGs) to access training, credentialling and licensure, and a lack of mobility of physicians across Canada. Furthermore, data suggests that with increased administrative burden in practice, greater complexity of care, and inconsistent development of integrated, team-based care models, individual physicians are unable to care for the same number of patients as they could in the past.

Each of these problems requires different solutions. For example, three new medical schools are in development in Canada and many provinces are increasing the number of residency training positions. Although these steps will add new doctors in coming years, the long training cycle to complete medical school and residency means that this cannot be the only solution.

A quarter of physicians practising in Canada today received their medical degrees outside of Canada and this proportion has been stable for more than a decade. But data from the Medical Council of Canada shows that of the 1,700 IMGs who passed their exams last year, less than half of them found a way to enter the Canadian system. The Royal College is working closely with Medical Regulatory Authorities – the provincial and territorial colleges that provide licensure for physicians – as well as Health Canada, to address this situation.

We have three main pathways for IMGs, all of which are being modified or expanded.

Finally, across all pathways we have decreased the processing time for most applicants from an average of 6-18 months to 4-12 weeks. I am grateful to the Royal College staff for their incredibly hard work to reach this standard.

The Royal College is very concerned with Canada’s shortage of specialist physicians and we will continue to explore new ways to accelerate and evolve our pathways and processes. I look forward to sharing more on our progress in a future column.

Brian Hodges is the 47th President of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. He is the executive vice-president of education and chief medical officer at the University Health Network. A professor in the University of Toronto’s Temerty Faculty of Medicine and at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, as well as a senior fellow at Massey College, Dr. Hodges is also a practising psychiatrist.